We acknowledge all First Peoples of this land and celebrate their enduring connections to Country, knowledge and stories. We pay our respects to Elders and Ancestors who watch over us and guide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

Flora Nullius is an exploratory essay by storyteller Dakota Feirer which forms part of Common Ground's truth-telling series – Weaving Truths.

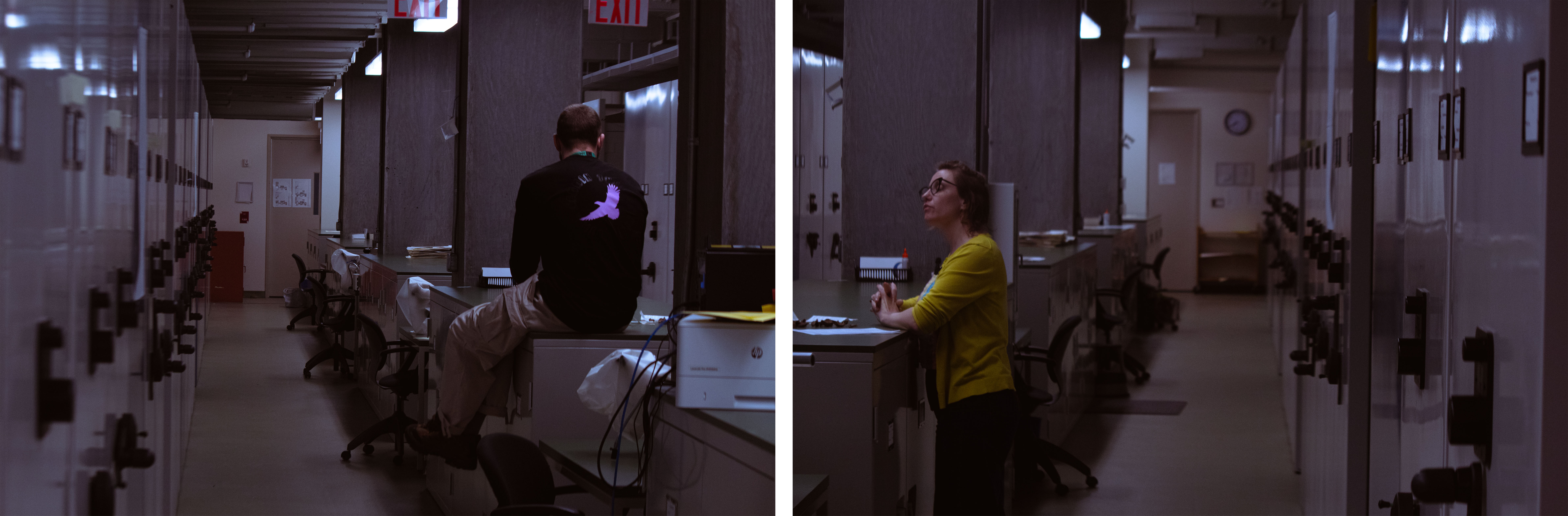

Dakota Feirer explores the myth of flora nullius in conversation with Laura Briscoe, assistant curator and collections manager of the New York Botanical Garden Cryptogamic Herbarium.

Together, they uncover truths through a botanical specimen collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, as part of the Plants of Captain Cook’s First Voyage 1768-1771.

Flora nullius is a concept similar to terra nullis, where control of naming plants suggests they weren’t known or didn’t have names before – irrespective of existing for millennia.

Dakota Feirer is a Bundjalung and Gumbaynggirr descendent based in Lenapehoking (New York City).

No colonial intervention can alter the truth of Country. – Jazz Money, 2022.

Soft hues of lilac, daffodil and magnolia have arrived at a complete and synchronous bloom. Foraging along the grounds are a caucus of chipmunks, squirrels, birds and other common North American woodland creatures. Along the waters: turtles, ducks and geese are basking in the warmth of a new Spring sun. At once this floral world pirouettes whilst humming its song of life.

The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) contains the largest tract of remaining forest in the city of New York. For my final research visit to the Garden, I am intentional about observing the subtle acoustics of the Bronx River, the afternoon sunlight dancing through the trees, the unapologetic aroma of fresh pollen, and the romantic tension between an old remaining forest and its near backdrop of a constant, metropolitan noise.

Although surrounded by an encroaching, industrialised world, the land lets us know that Spring has arrived. Overlooking this dance, a climate-controlled archive pulses with the echoes of a more distant Country. This particular day was a reminder of the inalterable truth of Country: it remembers.

Dakota: I have spent many hours in this building, in this room, unpacking the stories, the data, the memories that are shelved in this format...

Laura: An archive.

Dakota: That's right. Meanwhile, walking through one of the older archives… we spoke about the Magnolias and how they remember the dinosaurs.

I'd like to acknowledge that Country – place – holds memory. And acknowledging we're here on what has been told and referred to me as Lenapehoking, the Lenape territories.

Laura: I so appreciate the invitation for this conversation. It's also an invitation for me to remember the objects that I work with on a daily basis, so that they don't become flattened in their scale.

Laura: My name is Laura Briscoe. I am an assistant curator of the Herbarium, which is a natural history collection comprised of scientific collections of plants, algae and fungi.

I say ‘scientific collections’ because that is the context in which these gatherings were made and why they found their home here. Although, I think of them as much more than that… these objects have been situated evolutionarily and ecologically, but not culturally or historically.

By now the sun must be set, yet it is impossible to know. Laura and I are illuminated under bright fluorescents, a large examining bench divides the space between us. Numerous cabinets sprawl the length of the room, leaving the imagination to grapple with an ominously large scale of material. The room has a clinical, laboratory-like texture to it. Time collapses and disappears here.

Dakota: The building that we're in, what does it contain? Where does it come from?

Laura: [NYBG] is a cultural institution that was formed at the turn of the 20th century. There was a real desire in the community of European Americans who were practising botany to have a place that might rival the other institutions of note – such as the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, England and the Natural History Museum in Paris – both of which held collections that were global in scope because of the colonial powers of those nation states. They succeeded in that goal and formed this institution.

Simply put, a herbarium is a collection of preserved plants that are catalogued and stored systematically. They are regarded as vital sources of information about plants – including “where they are found, what chemicals they have in them, when they flower, what they look like” – while also serving as an index for the identities of plants, making them crucial for upholding a universal taxonomy of plant biodiversity. The NYBG houses the largest herbarium in the western hemisphere.

Laura: So, [NYBG] is one of the larger collections of its kind in the world, within the ballpark of 7 million collections.

Dakota: Of those 7 million… at least 40,000 [specimens] were taken from Australia. That is quite a large amount of material and it's something that, as an Indigenous Australian man, I don't even grow up thinking about… For what reason? For whose story? Who's benefiting from this process?

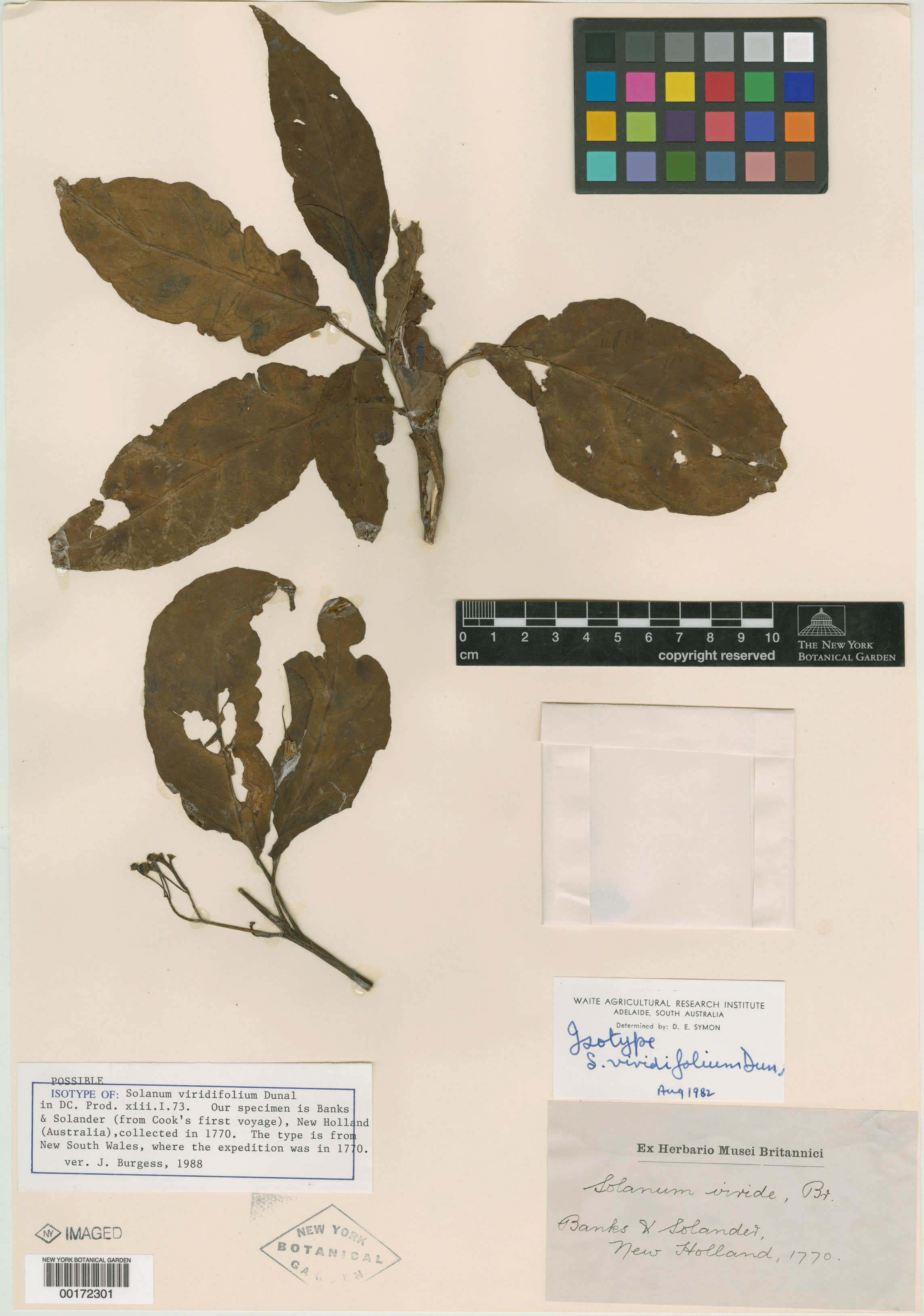

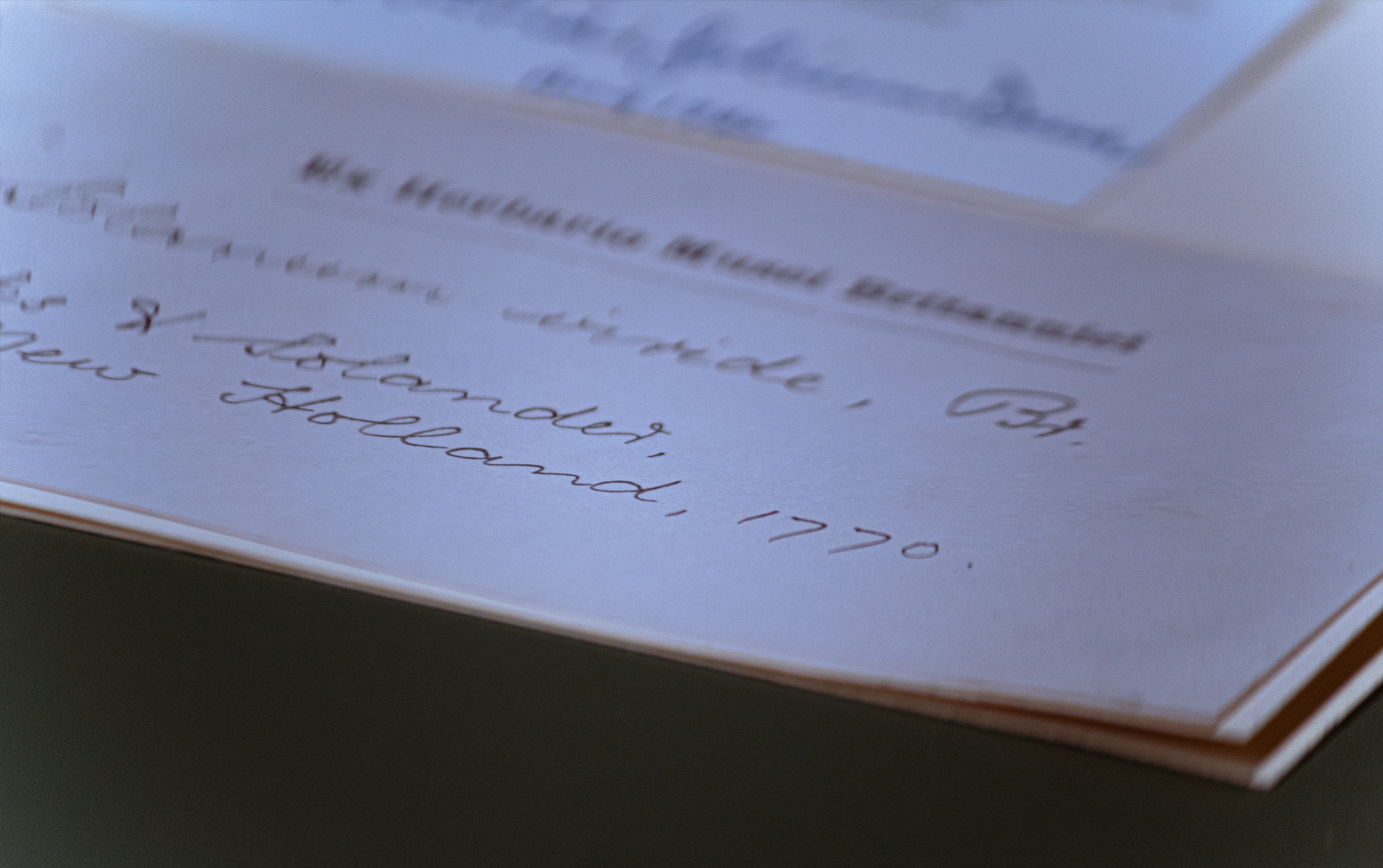

Laura gestures in the direction of a manila folder that’s been waiting patiently beside us. We open it together. In so doing, we take a giant leap backwards in time, landing on the eastern coastline of Dharawal Country, Kamay (Botany Bay), the year 1770.

Collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, as part of the Plants of Captain Cook’s First Voyage 1768-1771.

Laura: So, this is a collection of a plant that we think of as Solanum viridifolium… collected by “Banks and Solander” in “New Holland 1770.”

Dakota: It was minding its own business at one stage.

Laura: Just growing, flowering, fruiting and then Banks and Solander came.

In the 18th century, naturalist Joseph Banks and botanist Daniel Solander accompanied lieutenant James Cook aboard the HMS Endeavour. The official task of the voyage was to map the transit of Venus through the Southern Hemisphere. However, there was a secret mission involved, communicated in the form of a sealed letter from the Admiralty.

Cook opened this letter once the celestial observation of Venus was complete, revealing a secret directive: to locate and claim the southern landmass, Terra Australis Incognita. The letter with instructions from the Admiralty asks that Cook and his party observe the local Indigenous population and “endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a friendship and an alliance with them…”

The orders also requested:

You are to also carefully observe the nature of the soil, you are to bring home specimens of each as also such specimens of the seeds of the trees fruits and grains as you may be able to collect and transmit them to our secretary that we may cause proper examination and experiments to be made of them.

Banks recruited Solander – a student of Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish Naturalist and grandfather of Linnaean taxonomy – because of his taxonomic expertise. Overall, Banks and Solander collected 30,000 plant specimens during the voyage, all of which were received for processing by the ‘Ex Herbario Musei Brittannici’ or the ‘The Herbarium of the British Museum’. Today they are known as the Plants of Captain Cook's First Voyage 1768-1771, which remain scattered across Herbaria throughout the world today.

Dakota: Why correct things? Why tell the truth?

Laura: Why not?... I think some people really only care about the name of the plant... “Who is this plant? What is the name of this species?”

But that's not the only piece of information that's being stored in these archives of natural history. Each collection and gathering has another history that it is witnessing, of the people who were in this place at this time… and there's a story there.

So, if we know the story, I think it's part of our job to tell that story… for authentically contextualising these gatherings, understanding when harm has been done through the acts of scientific collection or through the narratives that have been formed.

As we dig deeper at the roots of this plant ancestor, a cold reality swells to the surface. Its existence itself is haunting, as it appears relatively unchanged from when it was first uprooted by Banks and Solander, in the dusk of Cook’s voyage. This little bundle of Country is an echo of the first boot prints of the settler colony that would soon become Australia. It now exists as property of the NYBG, where it’s chemically preserved with pesticides and ontologically preserved with taxonomy.

Dakota: The power to name is the power to control, as if everything didn't have a name already. There was this idea of flora nullius to be occupied.

Solanum viridifolium is a symbol of the instrumental role of botany in the colonial project of Australia. It is a silent monument to the ideal of terra nullius, which depended on the erasure of Indigenous peoples and our own taxonomies of naming, kinship, moieties and various other systems of ordering the world and relating to Country. It is part of the settler production of flora nullius: the denial of Indigenous sovereignty in order to imagine Australia’s biodiversity as property of the Crown.

Laura: I think the bigger picture of the Linnaean legacy is that the species are nested within genera, which are nested within families, which are nested within orders, which are nested within classes. More than codifying this binomial system, [Linnaeus] codified hierarchy.

Within that hierarchy, implicit is the human relationship to nature, as you said earlier, that nature – even by calling it that – becomes somehow [separate] from the human experience, that nature is the other.

And that is unconsciously informing a lot of the ways that botanists are looking at these things. And the process of naming is through a very hierarchical lens.

Our biodiversity, which vitally encompasses our foods, medicines, totems, stories, traditional practices and ceremonies, has historically been sustained through non-hierarchical, intimate and local social structures of Lore, kinship and totemism. Though Solanum viridifolium represents a departure from such custodial human-nonhuman structures. It marks the moment Country became the target of possession and exploitation by the colonial nation state.

This ideal persists in the ongoing commercialisation of native botanicals – including flowering and fruiting plants, fungi, lichens, algae and mosses – throughout, but not limited to, the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and commercial food industries. For example, within the $600 million Australian native foods industry, less than 1% is owned by Indigenous peoples.

Economic botany, the study of ‘useful plants’, played a crucial role in the expansion of the British Empire, and often exploited Indigenous lands, peoples and their knowledges. This involved the production of plantations, monocultures and mass agricultural economies that relied on countless unethical practices, amongst them being enslaved labour and forced dispossession of land. It also depended on a network of botanic gardens that mapped and circulated the world’s most vital natural resources.

For example, the botanical ‘discovery’ of rubber allowed for its industrialisation and resulted in the Rubber Boom of the late 19th century. This involved the exploitation of Hevea brasiliensis, or the rubber tree, which was utilised throughout local Indigenous groups across the Peruvian, Brazilian and Guyanese Amazon rainforest.

The resin – caoutchouc – derived from the rubber tree by the Omáguas peoples, was documented during a European expedition and sent to Paris for scientific analysis. This later resulted in a complex network of seed theft, indentured labour and the dispossession and deforestation of land for rubber tree plantations.

Other everyday products with parallel histories include sugar, cotton and tea. All of which have deep ties to colonialism and have caused long-term trauma, and in some cases, irreversible loss of local species and ecologies.

Across the world, extracted bodies and environmental knowledge – produced from Indigenous Country – constitute the laboratories and archives of natural science and history. These disciplines are not immune to the harmful structures that trouble our history. In fact, they are still dealing with legacies of harm that continue to exclude, exploit and erase Indigenous peoples and our knowledges.

Dakota: What's that responsibility mean to you? What is truth-telling to you and your family?

Laura: I think I also assumed that the primary responsibility for caring for these collections was keeping them physically safe and sound... But my own personal praxis has shifted to be more intersectional and to understand and acknowledge places where harm has occurred… to try to find opportunities for repair…

But to hold a thread of respect… and to somehow hold a tension between intention and impact. It's never okay to rest only on intention because the impact can be very real…

But there's a bravery that's needed, I think, to tell the truth… especially if it's not a story that you've been told or if you've actively been told things that are not objectively true, about history, or the history of western science, the history of any nation state. I think we've all experienced that in our own ways of being brought up with stories that may or may not be true.

Jazz Money reminds us that no colonial intervention can alter the truth of Country, and Country, in all its forms, remembers. It is our job to constantly attend to that memory and always learn from its stories. By holding respect for one another and showing bravery when confronting shameful histories, together we must walk toward horizons of repair. That walk starts with truth-telling.

James Cook & Great Britain. Admiralty, 1768. Cook's voyage 1768-71. National Library of Australia.

“Index Herbariorum,” New York Botanical Garden, accessed 9 April, 2025.

McDaniel, Emily. “Right of Reply,” Powerhouse, 2022.

McDaniel, Lachlan. “Powerhouse Late: Food Sovereignty,” Native Foodways, 2023.

Money, Jazz. Garrandarrang, 2022. Cited by McDaniel in “Right of Reply,” Powerhouse, 2022.

“What is an Herbarium,” Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, accessed 27 April, 2025,